COVID-19: Impact on cardiology procedural services

| Take Home Messages |

|---|

|

Introduction

On the 12th March 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared the novel Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak a global pandemic.1 The virus, known as severe acute respiratory syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), which genetic sequencing has revealed is likely to originate from bats, has changed the world in a dramatic fashion. The National Health Service (NHS) is no exception. Indeed, in many hospitals across the UK the division according to specialty is no longer present; rather hospitals are simply divided into COVID and non-COVID areas. Many hospitals have surrendered their coronary care and day-case units to facilitate expansion of intensive care resources; and non-acute doctors have joined colleagues from general medicine, emergency departments or intensive care to serve in the frontline battle against COVID-19.

In response to the COVID-19 pandemic Public Health England recommend that hospitals postpone non-urgent elective work and rationalise acute services.2 The present editorial provides an update on the impact of COVID-19 on cardiac procedures within the UK, and recommendations from the various British Cardiac Societies.

Protection against COVID-19 in the cardiac catheter laboratory

SARS-CoV-2 shares 75-80% of its viral genome with severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS-1) and middle eastern respiratory syndrome (MERS),3 which infect intrapulmonary epithelial cells more than cells of the upper airways.4 SARS-CoV-2 enters cells via the human angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 cellular receptor,5 however appears to be more virulent due to an enhanced ability to mutate.3 The basic reproduction number (R0) of SARS-CoV-2 is 2.28, significantly higher than SARS-1 and MERS (1.88 and 0.47, respectively).6 Transmission of SARS-1 and MERS occurs primarily from patients with recognised illness by means of large droplets and contact and less so by aerosols and fomites.7-9 The transmission of SARS-Cov-2 is assumed to be similar however there have been reports of transmission from asymptomatic carriers to cohabiting family members causing severe COVID-19 pneumonia, described as the “asymptomatic carrier” phenomenon.10-12 Concerns surrounding the spread of COVID-19 via healthcare workers has major implications for cardiac procedures.

Aerosol generating procedures can produce droplets <5 microns in size which, if inhaled can cause infection. Pathogens within air droplets can remain in the air and travel distance whilst still being infectious. It is critical that health care professionals working in the cardiac catheter laboratory know what type of personal protective equipment they should be using depending on the COVID-19 status of the patient and type of procedure (See Table 1 and Figure 1). Guidance is available from the British Cardiovascular Society (BCS) /British Cardiovascular Intervention Society (BCIS) / British Heart Rhythm Society (BHRS),13 as well as Public Health England14 and WHO.15

Table 1. Aerosol Generating Procedures requiring type 2 PPE | ||

|---|---|---|

World Health Organization15 | BCS/BCIS/BHRS13 | |

Definition | A medical procedure that results in the production of airborne particles (aerosols) which may be pathogenic. | Any procedure requiring or likely to require resuscitation for cardiac arrest involving CPR ± intubation and to transoesophageal echocardiography |

Examples | Cardiopulmonary resuscitation Non-invasive ventilation (i.e. BiPAP, CPAP) Intubation/extubation Bronchoscopy Induction of sputum Airway suction Chest physiotherapy | Angiography/PCI post cardiac arrest Primary PCI Complex PCI VT ablation Cardiogenic shock Transoesphageal echocardiography |

Guidance for health care workers undertaking aerosol generating procedures13-15 |

| |

BCS British Cardiovascular Society, BCIS British Cardiovascular Intervention Society, BHRS British Heart Rhythm Society, BiPAP bi-level positive airway pressure, CPAP continuous positive airway pressure, PCI percutaneous coronary intervention, PPE personal protective equipment, VT ventricular tachycardia, WHO World Health Organization. | ||

Figure 1. Appropriate PPE in the cardiac catheter laboratory according to BCS/BCIS/BHRS13 | ||

|---|---|---|

|  | |

Type 1 | Type 2 | |

Components | Apron, gloves, surgical face mask, eye protection (if closer than 2m to patient) | Sterile fluid resistant gown, gloves, FFP respirator face mask, eye/face shield |

Procedure type | Other procedures | Aerosol generating procedures |

Examples | PCI for stable ACS (e.g. NSTEMI), routine permanent pacemaker implantation, transthoracic echocardiography. | Primary PCI, intubated patient, high risk of cardiac arresta, VT ablation, transoesophageal echocardiography. |

a High risk defined as resuscitated cardiac arrest, haemodynamically unstable, admitted via emergency department resuscitation area. Acute coronary syndrome, BCS British Cardiovascular Society, BCIS British Cardiovascular Interventional Society, BHRS British Heart Rhythm Society, DC direct current, NSTEMI non ST-elevation myocardial infarction, PCI percutaneous coronary intervention, PPE personal protective equipment. | ||

Management of coronary artery disease

NHS England and NHS Improvement, with endorsement from the BCS ad BCIS have recommended to restructure cardiology services during the COVID-19 pandemic.15

For STEMI:

- postpone all non-urgent elective procedures;

- primary PCI should remain first line treatment for STEMI presenting within 12 hours of pain onset;

- out of hospital arrests should only be transferred to a primary PCI centre if there is clear ST elevation and no other significant co-morbidities;

- PCI centres that do not normally offer primary PCI for STEMI patients may undertake primary PCI during normal working hours;

- in patients with COVID-19 and STEMI primary PCI remains first line but thrombolysis can be considered on a case-by-case basis where significant ambulance delays are anticipated;

- patients can be managed in level 1 beds (i.e. cardiology ward, non-coronary care setting);

- inpatient echocardiography and cardiac rehabilitation assessment is not necessary for stable patients.

In ACS (not STEMI):

- acute coronary syndrome patients should be assessed on a case by case basis;

- the usual NSTEMI pathways including PCI should continue;

- optimal medical treatment without angiography for lower-risk NSTEMI patients and angiography in higher risk NSTEMI;

- three vessel disease should be treated with PCI;

- transcutaneous aortic valve implantation is preferred for treatment of severe aortic stenosis in acute situations.

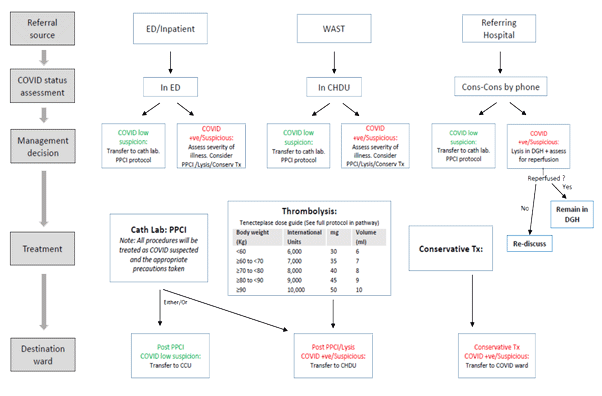

To incorporate these recommendations PCI centres may need to modify existing primary PCI pathways for the following reasons: to incorporate assessment of COVID status early in the pathway; catheter laboratory utility may fall in order to reduce foot fall; fewer staff due to redeployment, sickness or social isolation policies; and overstretched ambulance transport services. An example of a primary PCI pathway from a tertiary centre is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Example of a modified UK tertiary centre STEMI pathway

The STEMI pathway from the Morriston Cardiac Centre (Morriston Hospital, Swansea) was adapted in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. This centre has 3 catheter laboratories but only 2 are in operation since the pandemic. There is a separate “clean lab” for non-COVID patients and a separate “dirty lab” for suspected and confirmed COVID-19 cases. Each lab is deep cleaned after every procedure.

CHDU cardiac high dependency unit, conserv Tx conservative treatment, DGH district general hospital, PPCI primary percutaneous coronary intervention, STEMI ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction, WAST Welsh Ambulance Service Trust.

Cardiac rhythm management

Complex devices and electrophysiology considerations during the COVID-19 outbreak can be extrapolated from adaptations used for catheter laboratory procedures and PPE for high risk areas.11 In addition NHS England15 recommend:

- urgent bradycardia pacing and ablation of malignant arrhythmias should continue (i.e. high grade atrioventricular block, secondary prevention defibrillators, ventricular tachycardia ablation, generator replacements in pacing dependent patients, pre-excited atrial fibrillation);

- device/lead extraction should continue for infection (i.e. bacteraemia, endocarditis, pocket infection)

- decisions surrounding implantation of primary prevention defibrillators, or cardiac resynchronisation therapy for heart failure treatment is left to clinician judgement depending on the situation (see Table 2);

- use of remote monitoring of devices where possible.

The American College of Cardiology along with the Heart Rhythm Society COVID-19 Task Force and the American Heart Association's Electrocardiography and Arrhythmias Committee of the Council on Clinical Cardiology have also released new guidance for cardiac electrophysiology during COVID-1917 which mirrors our guidance here in the UK.16

Table 2. Electrophysiology and devices procedures categorised by urgency16 | ||

|---|---|---|

Urgent procedures | Semi-urgent | Non urgent (Elective) |

Catheter ablation

| Catheter ablation

| Catheter ablation

|

Cardiac devices

| Cardiac devices

| Cardiac devices

|

Other

| Other

| |

AF atrial fibrillation, AFL atrial flutter, AV atrioventricular, AVB atrioventricular block, CHB complete heart block, CIED cardiac implantable electronic device, CRT cardiac resynchronisation therapy, ED emergency department, EOL end of life, EP electrophysiology, ERI elective replacement indicator, ICD implantable cardioverter defibrillator, ICU intensive care unit, LAA left atrial appendage, LBBB left bundle branch block, PPE personal protection equipment, PPM permanent pacemaker, PUI patient under investigation for COVID-19, SND sinus node dysfunction, SVT supraventricular tachycardia, TEE transesophageal echocardiography, VT ventricular tachycardia, WPW Wolff-Parkinson-White. | ||

Imaging

Echocardiography

The British Society of Echocardiography have published guidelines on transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) and TOE in the COVID-19 era.26 The society reiterates concerns from its members with regards to aerosol spread given the very close face-to-face contact required during both TOE and TTE. It is recommended that TTE requests should now be triaged to perform only those that alter immediate medical management and can be level 1 scans (see BCS Editorial COVID-19: a practical guide to cardiac assessment and treatment).18 For patients with higher risk for COVID-19 a portable bedside echocardiogram is preferred. Access to elective echocardiography will be triaged on a case-by-case basis and performed in patients deemed at high risk (e.g. markedly elevated brain natriuretic peptide).

Cross sectional imaging

The European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging have produced guidelines regarding cardiac imaging during the COVID-19 pandemic.19 The key points from the guidelines are:

- elective, non-urgent investigations can be postponed;

- greater care is required to rationalise investigations in patients with suspected or confirmed COVID-19 infection;

- measures are advised to reduce risk of transmission including portable echocardiography, limited the duration of the study (focused) and appropriate PPE should be used;

- the potential role of cardiac computed tomography (CT) in the diagnosis of acute coronary syndrome in COVID-19 patients (i.e. raised troponin and suspected ACS), and can be performed at the same time as thoracic CT;

- cardiac magnetic resonance imaging can be used in the acute setting to identify cardiac pathology in COVID-19 patients (e.g. myocarditis, Takotsubo cardiomyopathy).

Availability of cardiac CT, CMR and nuclear imaging will depend on local services. In some centres CMR has been adopted as first line for functional assessment of ischaemic heart disease as the scanning protocols pose a lower risk for transmission of COVID-19 compared to stress echocardiography.

Future implications

The COVID-19 pandemic has dramatically changed cardiology practice within the UK which has immediate and future implications. Since the COVID-19 pandemic, there has been an acute decline in cardiac hospitalisations such as MI and stroke across the UK,20 likely as a result of patient fear of acquiring COVID-19 infection in hospital settings. Concerns have been raised as to whether these patients may be presently suffering in silence and are at risk of severe complications later during the pandemic. Public health initiatives are under way to try and encourage the general public to recognise serious cardiac symptoms and seek medical attention when needed.

There has been a restructuring of outpatient services with implementation of virtual clinics (e.g. telephone, video-conferencing), and remote monitoring instead of face-to-face visits where possible. These positive steps are encouraging however there is concern that cancellation of outpatient elective procedures may have serious consequences. Such patients may be at increased risk of: sudden cardiac death (e.g. primary prevention defibrillators); hospitalisation due to cardiac events (see Box 1); poorer outcomes due to postponement of intervention (e.g. aortic stenosis, atrial fibrillation ablation); receiving treatments associated with inferior outcomes (e.g. PCI in multivessel disease rather than coronary artery bypass surgery).

Box 1. Case – what are the consequences of postponing non-urgent PCI? | |

A

| B

|

Case An 80 year-old patient underwent elective PCI of left anterior descending artery for treatment of stable angina. Elective staged PCI of a severe proximal RCA lesion was scheduled but postponed due to the COVID-19 pandemic and subsequent NHS England recommendations. The patient presented 2 months following elective PCI with an inferior STEMI due to a thrombotic occlusion of the proximal RCA. Primary PCI was performed: a stent was placed within the RCA and the patient was discharged without complication.

Discussion PCI in the setting of stable angina has not been shown to reduce risk of future myocardial infarction when compared to medical therapy however in this case the patient had a high-risk unstable lesion as evidenced by the inferior STEMI presentation. A sub-group of high risk patients are more likely to suffer from postponing non-urgent PCI and identifying such patients will be challenging. | |

Coronary angiogram showing severe proximal RCA lesion (A) and acute thrombotic occlusion (B). NHS National Health Service, PCI percutaneous intervention, RCA right coronary artery, STEMI ST elevation myocardial infarction. | |

Finally, postponement of elective cardiology procedures has major implications for cardiology training within the UK. A recent BCS survey of primary PCI centres demonstrated that the number of cardiac catheter laboratories has approximately halved since the COVID-19 pandemic (unpublished data). Clinical research (excluding COVID-19) has largely stopped and many out of programme trainees undertaking research have returned to their original training centres. Cardiology trainees are likely to require extension of their training period to acquire competencies which may delay progression.

Conclusions

The COVID-19 pandemic has had an unprecedented impact on cardiac procedures worldwide and in the UK. The situation is rapidly evolving and the guidance is being updated continuously. It is likely that, as the number of COVID-19 positive cases increase, all patients presenting to hospital regardless of the symptom will be treated as potentially COVID-19 positive and the distinction between “low” and “high” risk of COVID-19 may cease to exist. It is also likely that we will become increasingly concerned with the non-presenters given the dramatic decrease in the incidence of acute conditions including myocardial infarctions and strokes that hospitals across the world have seen. A dynamic approach and information sharing between hospital trusts within the NHS and worldwide is going to be key in creating protocols and pathways that are constantly adapting to the COVID-19 pandemic.

References

- World Health Organization (WHO). Available: http://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/health-emergencies/coronavirus-covid-19/news/news/2020/3/who-announces-covid-19-outbreak-a-pandemic [Accessed April 2020]

- World Health Organization. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) Situation report – 76. 5th April 2020. Accessed online: https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200405-sitrep-76-covid-19.pdf?sfvrsn=6ecf0977_2 [Accessed April 2020]

- Public Health England. Reducing the risk of transmission of COVID-19 in the hospital setting. Available: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/wuhan-novel-coronavirus-infection-prevention-and-control/reducing-the-risk-of-transmission-of-covid-19-in-the-hospital-setting. [Accessed April 2020]

- Zhu N, Zhang D, Wang W, et al. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N Engl J Med 2020;382:727-733.

- Stanley Perlman. Another decade, another coronavirus. February 20th 2020. N Engl J Med; 382:760-762. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe2001126

- Zhou P, Yang X-L, Wang X-G, et al. Discovery of a novel coronavirus associated with the recent pneumonia outbreak in 2 humans and its potential bat origin. bioRxiv, January 23, 2020.

- Wu JT, Leung K, Leung GM. Now casting and forecasting the potential domestic and international spread of the 2019-nCoV outbreak originating in Wuhan, China: a modelling study. The Lancet. 2020. Available: https://www.thelancet.com/pdfs/journals/lancet/PIIS0140-6736(20)30260-9.pdf [Accessed April 2020]

- Peiris JS, Guan Y, Yuen KY. Severe acute respiratory syndrome. Nat Med 2004;10:Suppl:S88-S97.

- Hui DS, Azhar EI, Kim YJ et al. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus: risk factors and determinants of primary, household, and nosocomial transmission. Lancet Infect Dis 2018;18:e217-e227.

- Chan JF, Yuan S, Kok KH, et al. A familial cluster of pneumonia associated with the 2019 novel coronavirus indicating person-to-person transmission: a study of a family cluster. Lancet. 2020 Feb 15;395(10223):514-523. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30154-9. Epub 2020 Jan 24

- Rothe C, Schunk M, Sothmann P, et al. Transmission of 2019-nCoV Infection from an Asymptomatic Contact in Germany. N Engl J Med. 2020 Mar 5;382(10):970-971. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2001468. Epub 2020 Jan 30.

- Joseph T Wu, Kathy Leung, Gabriel M Leung, et al. Nowcasting and forecasting the potential domestic and international spread of the 2019-nCoV outbreak originating in Wuhan, China: a modelling study. Lancet 2020; 395: 689–97 Published Online January 31, 2020 https://doi.org/10.1016/ S0140-6736(20)30260-9

- BCS, BCIS & BHRS Response to PHE Updated Guidance on PPE. 6th April 2020. Available online: https://www.britishcardiovascularsociety.org/news/guidance-ppe-phe

- Public Health England. Guidance: COVID-19 personal protective equipment (PPE). April 2020. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/wuhan-novel-coronavirus-infection-prevention-and-control/covid-19-personal-protective-equipment-ppe

- World Health Organization. Infection prevention and control during health care when novel coronavirus (nCOV) infection is suspected. Interim Guidance, 25 January, 2020. Found online at https://www.who.int/publications-detail/infectionprevention-and-control-during-health-care-when-novel-coronavirus-(ncov)-infection-is-suspected-20200125

- NHS England and NHS Improvement. Clinical guide for the management of cardiology patients during the coronavirus pandemic. March 20th 2020. Last accessed 8th April 2020.

- Dhanunjaya R. Lakkireddy, Mina K. Chung, Rakesh Gopinathannair, et al. Guidance for Cardiac Electrophysiology During the Coronavirus (COVID-19) Pandemic from the Heart Rhythm Society COVID-19 Task Force; Electrophysiology Section of the American College of Cardiology; and the Electrocardiography and Arrhythmias Committee of the Council on Clinical Cardiology, American Heart Association, Heart Rhythm (2020), Epub ahead of print.

- Radhakrishnan A. A practical guide to assessment and treatment of cardiac conditions in COVID-19 patients. British Cardiovascular society. 17th April 2020. https://www.britishcardiovascularsociety.org/resources/editorials/articles/practical-guide-assessment-treatment-cardiac-conditions-covid-19-patients. [Last accessed 27th April 2020].

- Skulstad H, Cosyns B, Popescu BA, et al. COVID-19 pandemic and cardiac imaging: EACVI recommendations on precautions, indications, prioritization, and protection for patients and healthcare personnel, European Heart Journal - Cardiovascular Imaging, jeaa072, https://doi.org/10.1093/ehjci/jeaa072

- NHS England. A&E Attendances and Emergency Admissions 2019-20. https://www.england.nhs.uk/statistics/statistical-work-areas/ae-waiting-times-and-activity/ae-attendances-and-emergency-admissions-2019-20/

Community Events Calendar