Women in cardiology: where are we now?

| Take Home Messages |

|---|

|

Introduction

The under-representation of female clinicians in the field of cardiology has been a long-acknowledged and imperfectly understood topic.

In January of this year an editorial published in the European Heart Journal(1) examined data from the British Junior Cardiologists Association (BJCA) survey, amongst other sources, identifying challenges to addressing this complex issue.

In the same month, a session was dedicated to the topic at the Advanced Cardiovascular Intervention (ACI) conference, entitled ‘Women within Intervention - Facilitating Change and Optimising Opportunity’(2) , signalling renewed enthusiasm within the cardiovascular community for working towards parity in this emotive domain.

In this editorial we will examine the past, present and imaginable future of women in cardiology, the identified barriers to change and the potential and existing strategies designed to support further evolution in this area.

The Past

In 2005 the British Cardiovascular Society (BCS) working group published a report on women in UK cardiology(3) identifying that despite women outnumbering men at medical school since the mid-1990s, with 27.5% favouring cardiology as a career aspiration when surveyed(4), they remained under-represented in hospital specialties, particularly cardiology where they made up 16.8% of trainees and 7.4% of consultants.

It was identified that there was a discrepancy between expressed career preferences (27.5%) and the numbers of female registrars (16.8%), with no evidence of gender discrimination identified at the point of selection, indicating that women wishing to pursue a career in cardiology were being dissuaded at some point between medical school and specialty training.

A British Medical Association (BMA) survey done in 1995(5) highlighted the most common reason for a change in career choice was hours of work and working conditions leading the working group to conclude that “although the gap between the cardiological aspirations of female graduates and the numbers actually entering the specialty may reflect multiple factors, it is clear that a virtual ceiling composed of long, family unfriendly hours can be as hard to penetrate as one made of glass”.(3)

At this time, 95% of flexible training post-holders were women, citing childcare issues as the main reason for this.(3) Cardiology had significantly less trainees undergoing flexible training than other specialties such as anaesthetics, psychiatry and paediatrics (each with > 130 flexible trainees vs. cardiology with 6).

Though under-represented, numbers of female cardiology consultants rose progressively from 5% in 1992, to 7.5% in 2002.(3)

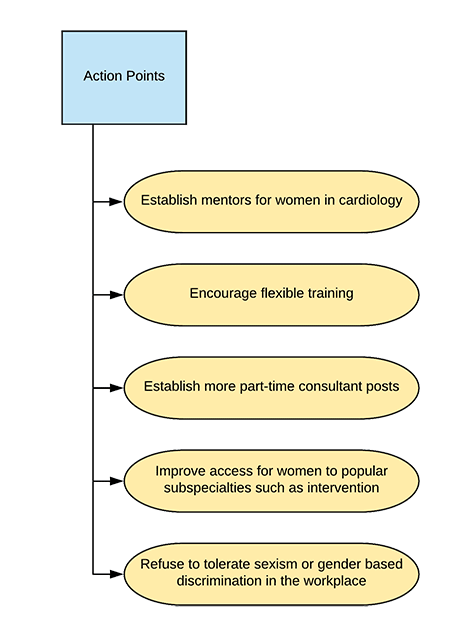

The working group proposed six possible solutions to the issue, the first of which required acceptance that there was a problem and recognition that if cardiology failed to attract female trainees when the undergraduate application ratio of male: female was approximately 1:1 it would miss out on a significant proportion of the talent pool.(3)

The remaining five action points are summarised in the table below (Table 1) with the intention of facilitating the recruitment of female trainees to the specialty.(3)

Table 1: Adapted from Timmis et al.(3)

The Present

In the recently published editorial, the authors examine data from the BJCA trainee survey, the GMC annual survey and data regarding admissions and progression from the Joint Royal College of Physicians Training Board (JRCPTB). They identified that, though still a minority in cardiology, the percentage of women has increased to 28% trainees, 13% consultants (from 16.8% and 7.4% respectively) though these proportions are amongst the lowest when compared to other medical specialties in the UK.(1)

In terms of sub-specialties, significantly fewer female trainees prefer intervention (29% vs 43% of their male counterparts) with a similar trend seen in electrophysiology (17% vs. 6% respectively) with imaging, heart failure and devices sub-specialties displaying the opposite trend.(1)

Addressing some of the action points raised in the 2005 working group report, the editorial reflects on the importance of relevant role models, citing a survey by Douglas et al. which highlighted their importance and impact on the career choices of female trainees.(6) They propose that in day-to-day practice, female role models, particularly in sub-specialties less popular with female trainees, are less common which may, in part, explain the perpetuated gender differences in sub-specialty choices.(1) Further supporting the notion of positive female influence and promotion of women in cardiology are the findings of a study examining sex disparities in authorship order of cardiology publications, which identified that “where women were senior authors, they published more articles with female first authors and had more female authors.”(7)

With relation to the final action point, refusing to tolerate sexism or gender-based discrimination in the workplace, the authors identify an interesting trend from the 2017 BJCA trainee survey; significantly more female trainees in ST5 (specialty trainee, year 5) posts (the year when sub-specialty choices are made, traditionally undertaken in tertiary centres) reported sexism than their ST3/4 counterparts (15% vs. < 6%). Further, significantly more trainees (male and female) working in tertiary centres reported experiencing or witnessing sexism than their district general hospital (DGH) counterparts, prompting speculation that this may be a factor influencing the subspecialty choices of female trainees.(1)

Finally, the authors report on the current state of flexible training, noting that, as per 2005, the vast majority of trainees working less than full time in the UK remains female (91.2%), with most applications to do so relating to childcare.(1)

The Future

As per Douglas et al’s survey findings, it would appear that the biggest obstacle to attracting female trainees into cardiology is the fact that women and future noncardiologists valued work-life balance more highly than their male and future cardiologist counterparts whose focus was found to be on the professional advantages and opportunities that a career in cardiology offers.(6) This, at least in part, relates to prevailing attitudes towards traditional gender roles within society, which, though improving (with 72% of the British public now disagreeing with the notion of women looking after the home whilst men earn the money, up from 58% in 2008) remain entrenched with 33% believing mothers of pre-school children should stay at home, 38% believing mothers should work part-time and 7% full-time, with these figures remining broadly static over the last 5 years.(8) Though attitudes towards shared parental leave between men and women are supportive, in practice it rarely occurs, indicates Nancy Kelley, the deputy chief executive of the National Centre for Social Research, adding that government must look beyond the law if they are hoping to balance child-rearing responsibilities between parents.(9)

Naturally, these issues are external to the sphere of influence of cardiology, but help go some way towards understanding the barriers to progression in attempts to attract diversity to the specialty, which is perceived by medical trainees in the United States as having ‘adverse job conditions’ and interfering with work life balance (6) with their London-based counterparts siting ‘inflexible hours’ and ‘competitiveness’ as negatively rated aspects of the specialty.(10)

The primary mechanism for attracting diversity into the specialty in this social climate is therefore working to alter the negative widely-held perceptions pertaining to a career in cardiology, a pre-requisite of which is improving the provision of flexible training opportunities and consultant posts, both for male and female cardiologists, promoting not only acceptance of, but encouraging flexible working to the benefit of all.(1, 11) Added benefit to this strategy may be its impact on physician burnout rates and workforce retention, with 24.1% of trainees reporting high or very high degrees of this attritional state in the 2018 National Training Survey.(12) Inroads are being made in this area with the BJCA including advice about less than full time training (LTFT) in the ‘National Cardiology Induction Handbook’ and focusing 2019 survey questions on issues facing LTFT trainees and women.(1) Concurrently the Cardiology Specialty Advisory Committee (SAC) is including considerations for LTFT training in future curricular design.(1)

Further initiatives aiming to improve gender diversity in Cardiology are underway. The BCS council includes a designated ‘Women in Cardiology’ position and both BCS 2018 and ACI 2019 conferences included sessions on the topic. At European level, the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) offers grants to facilitate attendance at the Women Transforming Leadership Programme and has commissioned a survey relating to gender, culture and leadership in cardiology to better understand the ongoing challenges faced in this area (13).

Conclusion

It is widely accepted that gender diversity in cardiology is beneficial and contributes to “the maintenance of high standards of practice and research” (11).

The challenges faced by women pursuing a career in cardiology remain similar, with the six action points identified by the working group in 2005 remaining as relevant as ever in 2019. While the numbers have improved, the trends remain comparable, though many stakeholders at deanery, national and international levels are working to address the gender imbalance in various ways.

Though societal factors affecting gender diversity are largely external to the sphere of influence of cardiology, there is much that can and should be done to promote flexible training and consultant job plans for both genders, to the benefit of all clinicians and patients alike.

References

- Sinclair HC, Joshi A, Allen C, Joseph J, Sohaib SMA, Calver A, et al. Women in Cardiology: The British Junior Cardiologists’ Association identifies challenges. European heart journal. 2019;40(3):227-31.

- British Cardiovascular Intervention Society. Advanced Cardiovascular Intervention 2019 - Programme 2019 [Available from: https://www.bcis.org.uk/aci-2019-homepage/aci-2019-programme/].

- Timmis AD, Baker C, Banerjee S, Calver AL, Dornhorst A, English KM, et al. Women in UK cardiology: report of a Working Group of the British Cardiac Society. Heart. 2005;91(3):283-9.

- Lambert T, Goldacre M, Parkhouse J. Career preferences and their variation by medical school among newly qualified doctors. Health Trends. 1996;28(4):135-43.

- British Medical Association. BMA cohort study of medical graduates 1995, 5th report. . London: BMA Health Policy and Economic Research Unit; 2000.

- Douglas PS, Rzeszut AK, Bairey Merz CN, Duvernoy CS, Lewis SJ, Walsh MN, et al. Career Preferences and Perceptions of Cardiology Among US Internal Medicine Trainees: Factors Influencing Cardiology Career Choice. JAMA Cardiol. 2018;3(8):682- 91.

- Ouyang D, Sing D, Shah S, Hu J, Duvernoy C, Harrington RA, et al. Sex Disparities in Authorship Order of Cardiology Scientific Publications. Circulation: Cardiovascular Quality and Outcomes. 2018;11(12):e005040.

- The National Centre for Social Research; Gender. British Social Attitudes 35 London: The National Centre for Social Research; 2018 [Available from: http://www.bsa.natcen.ac.uk/media/39284/bsa35_full-report.pdf].

- Gayle D. Survey finds UK is abandoning traditional views of gender roles United Kingdom: The Guardian; 2018 [Available from: https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2018/jul/10/survey-finds-uk-is-abandoningtraditional-views-of-gender-roles.

- Coyle C, Evans H. A career in cardiology: why? Heart. 2018:heartjnl-2018- 314292.

- Timmis AD, English KM. Women in cardiology: a UK perspective. Heart. 2005;91(3):273-4.

- General Medical Council. National training survey 2018 burnout questions: four country breakdown: General Medical Council; 2018 [Available from: https://www.gmc-uk.org/-/media/documents/national-training-survey-2018-burnout-questions-four-country-breakdown_pdf-76659211.pdf].

- European Society of Cardiology. Women in ESC 2018 [Available from: https://www.escardio.org/The-ESC/What-we-do/Initiatives/Women-in-ESC].

Community Events Calendar